Special shout-out and thank you to Daniel Tunkelang & Lucille Lam for their great support and feedback!

For Chief Technology Officer (CTO) candidates it can be hard to know what to expect from an interview process or how to go about it. In general, there’s one CTO per company, so not many opportunities for direct learning. Mostly, we need to learn from peers in our network. I’m sharing my recent experience here with a hope that other potential CTOs might benefit before embarking on their interview journey.

Not many folks, even CTOs, become deeply experienced at how to try to find the right job. During my process I kept detailed notes and decided to share this post-process read out. This is anecdata, biased in many ways, but I’ll offer generalizations that may be helpful to others; just keep in mind that applicability to your journey may vary. Along the way, I’ll propose lessons, which are based on this experience and my previous searches. Enjoy!

During this process 70 opportunities were presented. Of those, an astonishing 91% (64) were from external, executive search firms. Over the past 25+ years, networking has been an important part of my career and while there’s no clear metric, I feel well established in my relationship with investors, founders, and in-house recruiters. Nevertheless, only four opportunities (6%) manifested out of non-recruiter relationships.

Lesson 1: Do not rely on friends (professional or otherwise) for job opportunities.

Of the 64 external recruiter-driven opportunities, there were 17 unique search firms involved. The top five by number of unique opportunities were:

- Riviera Partners (29)

- Daversa Partners (7)

- True Search (5)

- Parker Remick (4)

- JM Search (3)

With well-established relationships at all five of those firms, it was not surprising to see their names at the top of my list (ie. bias in this data). Not working inside the firms, it’s unclear how well organized they are, how robust their individual usage of CRMs might be. Large firms like Egon Zehnder and Heidrick & Struggles were in my process, however with one and two opportunities respectively, it seems they’re not sharing candidate status internally. Lack of sharing is further reinforced when considering that — excluding the top outlier firm — the average number of opportunities per firm was 2.2.

Lesson 2: Long-standing relationships across multiple recruiting firms seems valuable; plus you get to help your colleagues when you’re not actively searching!

There were 56 different people (recruiters) involved, two of which were internal recruiters and eight of which I knew prior to this search. The average number of opportunities presented per recruiter for those I had just met was 1.15; while the average for recruiters I knew previously was 1.38. These are not statistically significant differences (p=0.17) so it’s unclear whether you’d see more opportunities from recruiters you know. However, you should ask your recruiter friends to share your search amongst their colleagues and then follow-up actively on those connections. Further to this point, again, excluding the outlying top firm, if we contrast the firms where I had a preexisting relationship with at least one recruiter (6 firms) vs. the firms where I had no preexisting relationship (10), they had more than 3x the average number of opportunities generated (3.8 vs 1.2), and this is not just stark but statistically significant (p=0.00).

Lesson 3: Ask recruiters (especially the ones you know already) to share your search within their firm and follow up proactively.

The first step in this journey–as in the past–was to establish an evaluation rubric. This tool was applied primarily during the initial call and then continuously referenced through each interview process. It was valuable preparation because every recruiter and almost every hiring manager asked me the same question: how am I evaluating opportunities.

You’ll want to make your own, but here is what I considered:

- (Objective) Is there a consumer experience and/or social impact factor?

- Mini-Lesson: Just about every business now claims to have social impact, most are stretching the definition

- (Objective) Will the compensation meet my requirements?

- (Subjective) Is it a fantastic team?

- (Subjective) Can I uniquely add value?

- (One I didn’t share; and only for privately held companies) Are the investors top-tier?

I declined to continue past the initial conversation 63% (44) of the time, most frequently because the business was not interesting to me (for one or more reasons usually due to the rubric described earlier). In a distant second, I declined because it seemed to me that they could find a better fit than myself. While it wasn’t by design, this indicated to me that my discussions during the initial call were useful, because, as a rough guide, if a stage gate blocks and permits roughly equally, it’s doing it’s job!

One further thought on the rubric: most recruiters really pushed for me to state what stage company I wanted; usually denoted in venture funding series or “mature”: private equity (PE), independent, or publicly traded. However, that is intentionally excluded from my rubric, it doesn’t matter to me. There were fascinating opportunities where I could create value in larger companies or in smaller. 15 (21%) of the opportunities were mature (series E or later, PE backed, public or equivalent) while 30 (43%) were series B-D. It’s likely coincidence, but opportunities progressed into the interview stage at exactly the same rate regardless of early or late stage (27% pass rate), which bolsters my rubric excluding stage. For other people, stage or scale may be a critical factor.

Lesson 4: Develop and apply a rubric, especially during the initial call, to screen out opportunities that you’re not excited about; don’t be overly permissive or restrictive.

For the first time in my career, compensation was used as a requisite factor for which opportunities to consider. It was a necessary component but not a sufficient component; and, it is relatively objective. So I raised this up front in the initial conversation. It became clear that most recruiters are pretty eager to find a way to make it work. And, unfortunately, later in the process, the actual hiring companies were less eager to be flexible. So half-way through my journey, I made a key change. I discussed the compensation issue with the hiring manager (usually the CEO) during my first conversation with them. This worked much better and quickly ruled out companies or I could opt out. There were many initial conversations where I declined and zero initial conversations where they declined (although two opportunities went dead for unclear reasons — perhaps that was their way of declining).

Lesson 5: If you have a strict compensation bar, bring it up with the hiring manager early and clearly; do not rely on the recruiter regarding compensation.

The compensation conversation can also be a launchpad to discuss the company’s compensation philosophy. As a department head, understanding their philosophy will be invaluable in building and maintaining an engaged team.

31% (22) of the opportunities moved beyond an initial conversation. It was fascinating how varied the processes were. Here are a few notes about my interviews:

- 18% (4) wanted case studies presented

- 9% (2) had a panel interview (multiple people meeting me at once) without a case study

- 23% (5) required travel during the process; interestingly at quite varied steps: one wanted it first, one wanted it last, the others were mid-process.

- Only once did someone propose (and follow through) to visit me!

While some people desire bringing multiple opportunities to the offer stage so they can create negotiating leverage, that was not my plan. My leverage was being patient and keeping to my rubric. Therefore as opportunities seemed a match, I kept them moving forward. Of those 22 opportunities, I was fortunate enough that five (23%) led to offers. Of these, I declined all but one; I mean, how else was that going to go? Of these offers, two were misaligned on compensation. That was frustrating and uncomfortable. In both cases compensation was not clarified up front and that helped reinforce Lesson 5 above, which was applied to later opportunities. Nevertheless, it was uncomfortable because not taking a great role due to pay is an awful reason, pragmatic though it may be.

These days, most companies are saying they’re fully remote or remote-friendly (only a couple explicitly said they were in-person only). After digging in, it frequently became more clear that policies were immature or ambiguous; and in some cases that, in reality, being in-person was critical.

- 96% (67) of the roles were described as “fully remote” and while it wasn’t extremely clear in all cases, most added the caveat “with regular in-person meetings” (ie. travel). Only one role was specific as 100% in-office. All but one role were domestic United States based (one was in the UK).

- Of the 22 opportunities that I interviewed for, plus seven others that were clear from initial calls (so 29 total), they broke out as:

– 55% (16) were truly remote roles (with at least quarterly travel for in-person meetings)

– 24% (7) said they were remote but required substantial in-person time (at least five days per month for the foreseeable future)

– 21% (6) were mostly in-office jobs, with flexibility to work from home when desired.

That’s about it for my journey — it was fascinating for sure! A few random other thoughts before sharing about selecting the new role.

Familiarize yourself with the Secretary Problem. In a theoretical vacuum, if one knew how many opportunities would be offered (and once offered they were guaranteed), and those opportunities could be ranked unambiguously, then one could use an optimal policy for when to stop interviewing and select a great role. In my case, if I knew there would be 70 opportunities (which I didn’t), then I could have potentially chosen well after 26 opportunities were considered. While this is hypothetical, there is a key lesson to be learned.

Lesson 6: Use each interview discussion to reduce ambiguity from your selection rubric and expect to make trade-offs.

The hiring managers and recruiters do not know how many other opportunities you’re considering, nor do they need to. However, they absolutely will detect the energy you bring to each and every discussion. Many colleagues and friends (particularly in non-C-level roles) have told me they find interviews exhausting. For me, interviews are enjoyable because I like meeting new people and love learning about companies.

The CTO role includes hiring and at growth stage companies it can be a big part of the job. In my experience more than 15% of my time is spent on the other side of the table, so it’s a comfortable setting. And when on the other side of the table, candidates sling all sorts of unstructured questions my way. As a result, I’m well practiced at answering a variety of questions. Moreover, the CTO role includes answering questions for journalists, for auditors, for customers, for the Board of Directors, for others throughout the company, and more. In other words, discussing various topics is important.

While there are many types of companies, if someone doesn’t like meeting with folks and discussing all sorts of random topics and answering questions, then the CTO job may not be the best choice. In the past, I’ve often had 50+ meetings a week… it’s a marathon.

Lesson 7: CTOs need to be excellent at interviews and should be well-prepared. If your energy can’t stay high doing lots of interviews, consider a different role.

Another perspective is that if you are not great at keeping your energy high, you should at least know how to manage yourself and to constantly re-fuel. In other words, learn how to avoid interview fatigue. There are lots of ideas online, but some include: avoiding back-to-back interviews, walk around between, listen to some comedy, whatever makes you happy. I personally love interviewing, it’s a pleasure to learn about businesses and people.

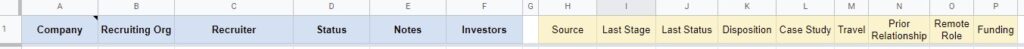

Lastly, it’s important to not lose the details or confuse opportunities. Take incredibly detailed notes. It’s pretty easy on video calls, because one can type while talking. It’s harder during in-person interviews, but you can jot down some notes during the conversation (on paper) and immediately after the interview(s), fill in the details as best as possible. You can also use a spreadsheet to track opportunities, link to your documents of notes, and track statuses and follow-ups. My approach is to use a single, running Google document per opportunity. It functions like a journal with a timeline and you can assign yourself action-items.

the “notes” column links to a separate google doc per opportunity

Lesson 8: Record detailed notes, stay organized, and don’t drop the ball. When you start the job this info will be invaluable!

You can learn more about the new company in an upcoming post. In the mean time, let’s look back to the rubric (from Lesson 4):

- Is there a consumer experience or social impact factor? BOTH!! In fact, the social impact is amongst the greatest of any of the companies I’ve met, and the consumer experience is fundamental to the success.

- Will the compensation meet my requirements? Yes! It was not the highest offer, but I had a high bar and it was over the line. Remember: trade-offs.

- Is it a fantastic team? Yes! I was astounded by each person on the team and how well they gelled. From the CEO across the whole group, each person really spoke to the culture in a brilliant way.

- Can I uniquely add value? Yes! Or, well, we’ll find out, but I believe so.

- Great investors? Yes!

So, in the end, I’m extremely psyched. Each aspect of the rubric was satisfied and beyond. Stay tuned for next time when I share the new role and more info!

Thank you for reading! Please e-mail me any feedback, it’s greatly appreciated (I may edit this post based on it)!

And before we go, here’s an overview of my whole journey: